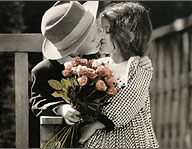

| Category - First Love Essay by Phillip Lopate To the child, Love is both real and a pretense: a necessity sometimes, a role at other times; instinctive, yet learned behavior. I see my little girl offering her hand to be kissed, in a very la-di-da manner. She is trying on the gallantries of love, just as she tries on the petulance of childhood. How quickly they master the social codes of love, hugs, and kisses, and hearts - as quickly as they learn to manipulate the heartstrings by refusing such tokens. All around children, there are cultural signals, prompts to express and receive love: in fairy tales, it is the ultimate reward for being discovered as who you really are, the beauty under the cinders, the prince beneath the frog. In advertisements, every product sold with the promise that its purchase will bring or enhance true love. At the same time that these diaphanous romantic feelings are being planted, there is the hot, urgent need of the child to be listened to, have needs attended to, right away. "Mommy I need a pair of scissors ANTZ is coming out on videotape. I'm hungry I pooped in my pants change me no stupid daddy not that kind of crayon the other kind!" All demands are on the same plane of importance, and worthy of tears. The child does not prioritize but asks only to be obeyed, pronto - with all die respect to the "magic words" please and thank you, those road-bump nuisance placed by parents, who are slow-witted and don't understand that they are your servants. It's frustrating sometimes that they won't acknowledge it; they do so much for you as it is, why won't they just come clean and admit they are you abject slaves? And in return you love them, distractedly, wholeheartedly, ambivalently ("I hate you Mommy! I'll never kiss you again for the rest of my life!") and in the best possible way, organically, like a heliotrope plant. So your first love as a child is for your parents. They thermodynamic model seems to be: love in, love out. If the parents' love has been expressed cleanly, without mixed messages or scary anger or abandonment (it almost never is, the psychologists tell us), the child will grow up into a serene, unconflicted adult; and if there are complications (there almost always are), the child will probably grow up to have "unresolved issues." But some confusion is inevitable: before you even reach kindergarten, you may very well have conceived the idea of marrying one of your parents later on (and why not? - he/she is so conveniently present, so attractively devoted to your needs); and you may have experienced jealous annoyance at their displays of affection to each other. As my four-year-old daughter Lily said to me this morning, when I had the nerve to kiss her mother in front of her, "That was the longest, rudest kiss I ever saw!" My daughter went through a quandary around the time she turned three. Who should she marry? she began to fret. I was an early candidate, I am happy to say. She enjoyed slow-dancing with me to Ella Fitzgerald and got a dreamy look in her eyes when I held her aloft in my arms. But she accepted (all too sanguinely, it seemed to me) the information that she could not marry her daddy because it just wasn't done. So her attention turned to other suitors. Her principal beam was the boy next door, Dominick. This kid is a lout. He barely speaks except to grunt, he is fixated on trucks, he regularly gets into trouble at play school for fighting. I tell you frankly, he is beneath my daughter in intelligence and deportment. Yet she professes to love him and plans to marry him. She tells me he will not always be so wild, he will make a good man when he grows up. He seems to possess that masculine je ne said quoi, that essence of machismo that even four-year-old girls are attuned to. I try to interest her in the more intellectual boys in her circle, but she pays them no mind. I will say this for young Dominick: he does seem to behave better around Lily, and, in his own way, appears fond of her. Still, I wonder how to protect her from the pain of unrequited love. The other day, Lily wanted to go to the neighborhood park because she thought Dominick might be there. "He loves the park, almost as much as he loves me," she said confidently. When we finally caught up with him, he seemed, from my vantage point, to ignore her - tearing back and forth on his bike, while she pretend he was chasing her. When she got tired of running from his approach, she sat on a bench and watch him. She was in no way put off by his self-absorption; rather she seemed able to weave his mere presence into her ongoing fantasy that he is crazy about her. When she first began asking "Who should I marry?" I was not the only one to tell the question might be a little premature. Our assurances did nothing to quell her sense of urgency. Obviously she had reached a development stage in her own mind when the act of deciding about something big - the choice of a life partner - had to be undertaken, at least in practice. I knew where some of the romantic suspense was coming from. She had chronically watched five different versions of Cinderella on tape from Betty Boop to Brandy, then had graduated to obsessions with The Sound of Music, Funny Face, Gigi, and My Fair Lady. One day, she remarked, like a precocious narratologist, "You know, they're all the same story." It was true: in each variation, a lowly girl had been plucked from the chorus, so to speak, to marry the top man. A few other candidates for Lily's hand had to be evaluated. Lily's great-uncle Reuben regularly proposed that they run away and get married, but he was over seventy and has a hearing aid; and besides, there was Aunt Florence, his wife of forty-five years, to consider. Then her pediatrician, Doctor Monti, expressed interest, but he was always so busy. No, it would have to be Dominick. Now that dilemma was settled, Lily began mulling over her wedding gown, tiara, pumps, jewels, boa, tutu. Wedding announcements would have to be sent out, ribbon bows tied, handwriting of name practice. She began to tell everyone who came to visit; "I have a boyfriend name Dominick and we're going to get married." Did this mean that she was infatuated with Dominick? On the contrary, during this time she had little contact with the actual boy, nor did she seem to want more. Meanwhile, I witnessed her daily eruption of intense feelings for another love object altogether: her cat, Newman. She could not get enough of catching him, snuggling with him, holding him captive by the paws, tying kerchiefs on his head, strapping blankets to his body, tormenting him in every possible fashion, and sobbing when he ran away. Here, I thought, was the real thing: love without the romantic gauze, but with the cruelty and appetite of attraction that one sees in film noir. She would kill for him - or kill him! How often my wife and I have had to intervene to protect the creature, removing from his neck harnesses and cravats that could have easily turned into nooses. Yet he always comes back to her, like the poor sap Glenn Ford used to play in those films noir, for more punishment. He craves her attention; and she, in turn, related to him fearlessly, accepting whatever scratches may come her way. Lily loves Newman in a deep, passionate manner. It is like a cross between her instinctual, inadvertent love for her parents and her elective affinity for the little boyfriend next door. Thought the Abyssinian has been with her all her life, her feelings have increasingly focused on and matured toward him: she talks to him regularly as though he were her child, her honey, her one and only. The problem is that Newman is twenty years old - ancient by cat standards. Already he is arthritic, cataract, and worrisomely skinny. He sleeps for much of the day, curled up in a ball, until Lily comes around to prod him into motion. As parents, we can try to protect our child from viciousness and harm, but not from the consequences of tender attachment. We shudder to think of what will happen when he dies. Then she will really know the sorrow that is so often inextricable from first love. |

|

Categories |

|

First Love << Thoughts << Friendship << Let's Pretend << Little Girls << Little Boys << Image Collection << Multimedia << About the Artist << Purchase the Book << Kim Anderson Links << Contact Me here << Return to Main Page << |